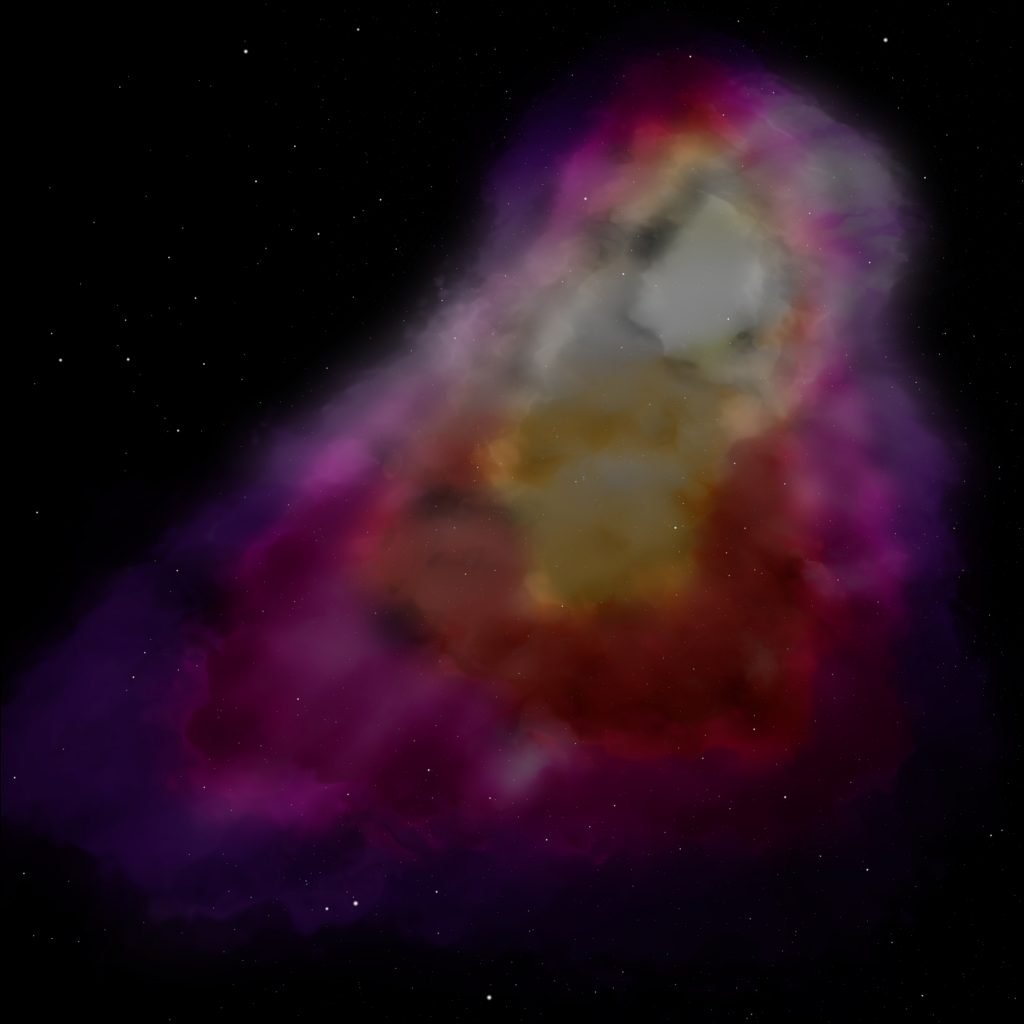

An international team of scientists has pushed the limits of radio astronomy to detect a faint signal emitted by hydrogen gas in a galaxy more than five billion light years away—almost double the previous record.

Using the Very Large Array of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in the US, the team observed radio emission from hydrogen in a distant galaxy and found that it would have contained billions of young, massive stars surrounded by clouds of hydrogen gas.

As the most abundant element in the Universe and the raw fuel for creating stars, hydrogen is used by radio astronomers to detect and understand the makeup of other galaxies.

However, until now, radio telescopes have only been able to detect the emission signature of hydrogen from relatively nearby galaxies.

“Due to the upgrade of the Very Large Array, this is the first time we’ve been able to directly measure emission from atomic hydrogen in a galaxy this far from Earth,” lead author, Dr Ximena Fernández from Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, said.

“These signals would have begun their journey before our planet even existed, and after five billion years of travelling through space without hitting anything, they’ve fallen into the telescope and allowed us to see this distant galaxy for the very first time.”

As an archaeologist digs down they find older and older objects. The same is true for astronomers—as they build bigger telescopes and develop new techniques to see farther into the Universe, they look further and further back in time.

“This is precisely the goal of the project, to study how gas in galaxies has changed through history,” Dr Fernández said.

“A question we hope to answer is whether galaxies in the past had more gas being turned into stars than galaxies today. Our record breaking find is a galaxy with an unusually large amount of hydrogen.”

This success for the team comes after the first 178 hours of observing time with the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope for a new survey of the sky called the ‘COSMOS HI Large Extragalactic Survey’, or CHILES for short.

Once it’s completed the CHILES survey will have collected data from more than 1,000 hours of observing time.

In a new approach, members of the team including Dr Attila Popping from International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research and the ARC Centre for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO) in Australia are working with Amazon Web Services to process and move the large volumes of data via the ‘cloud’.

“For this project we took tens of terabytes of data from the Very Large Array, and then processed it using Amazon’s cloud-based servers to create an enormous image cube, ready for our team to analyse and explore,” Dr Popping said.

Professor Andreas Wicenec, head of the Data Intensive Astronomy team at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, said the limiting factor for radio astronomers used to be the size of the telescope and the hardware behind it.

“It’s fast becoming more about the data and how you move, store and analyse vast volumes of information,” he said.

“Big science needs a lot of compute power—right now we’re designing systems to manage data for several large facilities around the world and the next generation of radio telescopes, including China’s 500m radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array and the SKA’s pathfinder telescopes that are already up and running in outback Western Australia.”

The study involved researchers from the US, Australia, the Netherlands, Germany, Korea and Chile, and was published today in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

More Information

The previous record was set in 2014 when two researchers from Swinburne University used the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico to detect atomic hydrogen in a galaxy three billion light years from Earth.

The Very Large Array is one of the world’s premier astronomical radio observatories and is managed by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in the United States. It consists of 27 radio antennas in a Y-shaped configuration on the Plains of San Agustin in New Mexico. Each antenna is 25 metres in diameter. The data from the antennas is combined electronically to simulate the resolution of an antenna 36km across, with the sensitivity of a dish 130 metres in diameter. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

The International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) is a joint venture between Curtin University and The University of Western Australia with support and funding from the State Government of Western Australia.

CAASTRO is a collaboration between Curtin University, The University of Western Australia, the University of Sydney, the Australian National University, the University of Melbourne, Swinburne University of Technology and the University of Queensland. It is funded under the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence program and receives additional funding from the seven participating universities and the NSW State Government Science Leveraging Fund.

Professor Jacqueline van Gorkom leads the CHILES team and is a researcher with Columbia University in New York. Her main interest is in the structure and evolution of galaxies, and more specifically in the role of gas in galaxy evolution. CHILES is partially supported by a collaborative research grant from the National Science Foundation.

Dr Attila Popping is a member of the CHILES team and a researcher with the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth, Western Australia. His main interest is the evolution and distribution of neutral hydrogen in the Universe.

Dr Andreas Wicenec is leading ICRAR’s Data Intensive Astronomy program to research, design and implement data flows and high performance computing systems for current and future observatories.

Original publication details

‘Highest Redshift Image of Neutral Hydrogen in Emission: A CHILES Detection of a Starbursting Galaxy at z=0.376, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Contacts

Dr Attila Popping (The University of Western Australia, ICRAR, CAASTRO)

Ph: +61 420 686 215

E: Attila.Popping@icrar.org

Dr Ximena Fernández (Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey)

Ph: +1 (848) 445 8898

E: ximena@physics.rutgers.edu

Prof. Jacqueline van Gorkom (University of Columbia, New York)

Ph: +1 (212) 854 6850

E: jvangork@astro.columbia.edu

Prof. Andreas Wicenec (University of Western Australia, ICRAR)

Ph: +61 431 832 602

E: Andreas.Wicenec@icrar.org

Kirsten Gottschalk (Media Contact, ICRAR)

Ph: +61 438 361 876

E: kirsten.gottschalk@icrar.org

Multimedia

Click each image for highest resolution.